When I was six years old, my father’s job took us from South Africa to the United States. The year was 1976, and South Africa was reeling from the Soweto uprising, a student-led protest against the Apartheid government that ended in the deaths of at least 176 Black school students, with thousands more being injured.

Being a six-year-old child on the privileged side of Apartheid, I didn’t really know what was going on. I was vaguely aware of something big happening in the news, but I didn’t know what any of it meant. At that age, all I really understood about Apartheid was that Black people only ventured into white neighbourhoods if they happened to work there, usually as someone’s maid or gardener.

When we moved to a quiet suburb of Connecticut, things didn’t seem much different. The small town we lived in was decidedly WASP by nature. Formalized Apartheid may not have existed in Connecticut, but the segregation was just as real. If anything, I had even less contact with Black people in the United States than I ever had in South Africa.

My first week of school in Connecticut was uneventful – until the bus ride home one afternoon. What my brother and I didn’t know was that some of the other kids on the school bus were hiding rocks. As we got off the bus, these kids stood up and threw the rocks at us, taunting us for being the bad South African kids. I remember walking from the bus stop to our house under the protective arm of my brother, with blood gushing from a wound on my head.

It took many years for me to understand that as traumatic as that experience was for me, it was a curious embodiment of the privilege that I had grown up with. For us, this was an ugly isolated incident. For Black South Africans back home, being on the receiving end of attacks like that was a part of everyday life. They woke up each morning with no real certainty that they would still be alive at the end of the day.

When we returned to South Africa, I was three years older than when we had left. I was beyond the age of accepting things without question: now I was observing the world around me and asking questions about what I saw.

When my mother was driving me to school one morning shortly after our return to South Africa, we were stopped at a traffic light. As we waited, a police van drove up and parked on the shoulder, where several Black people were walking and chatting to each other. Two police officers jumped out of the van and approached the group. A few of the people showed papers to the police officers and were allowed to go on their way. The rest were forced to get into the back of the van.

“What did those people do wrong?” I asked my mother, as the van drove off, leaving a cloud of desperation in its wake.

“They didn’t do anything wrong,” said my mother. She looked immeasurably sad.

“So – why did the police take them away?”

“Because they’re not supposed to be in this area.”

When I got home from school that day, my mother offered me a fuller explanation. I got a lesson about “pass laws”, a draconian set of rules that made it illegal for Black people to be in white neighbourhoods without documented proof that they were employed by someone there. What I had seen was a typical police arrest of people who were, quite literally, in the wrong place at the wrong time.

As I adjusted to being back in South Africa, I frequently saw these arrests taking place. It bothered me every time, especially in the context of other hallmarks of Apartheid South Africa. The Group Areas Act, for instance, meant that South Africans were allocated areas that they could live in. The land allocated to white people was proportionately far greater than that set aside for other races. This led to chronic overcrowding in most of the Black neighbourhoods, which in turn resulted in a shortage of resources like water and access to healthcare.

From time to time, the government would reallocate land, usually in favour of white people, and whoever was living on that land would be forcibly removed. In many cases, there would barely be time for families to gather whatever belongings they could before bulldozers moved in and destroyed their homes right in front of them.

I was too young at the time to understand anything about politics, or to question why such grave human rights abuses were being allowed to take place. My parents, like other white people of their generation, couldn’t speak out for fear of losing their jobs, and possibly their freedom. But when the wheels of change finally started turning during the 1980s, the vast majority of white South Africans were in full support of reform.

The abolition of pass laws in 1986 was a major turning point for the country. That era also saw an end to the prohibition on interracial marriage, and the desegregation of public facilities such as parks and public restrooms.

There was still a lot of work to be done, though. The fight for change was not over. My aunt, who in earlier days had lost her position as a teacher because she refused to recognize the national anthem of an oppressive government, spoke to me about complicity.

“Every white person in this country who does not contribute to change is part of the problem,” she said.

I carried these words with me to university, where student protests against Apartheid were the norm. I was not a central figure in the protests by any means. I was never the one standing up front with a megaphone and an angry message, but I was there. I was part of several crowds speaking up for reform, demanding the unbanning of Black-led political organizations, calling for equal voting rights for all.

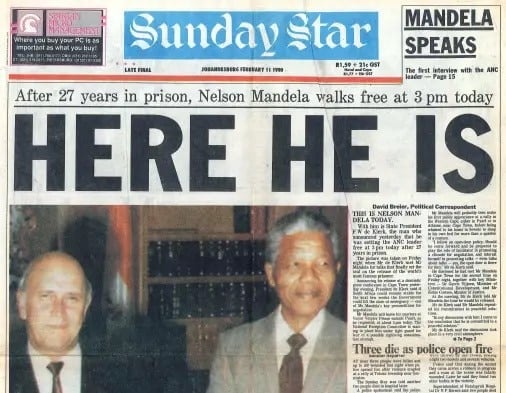

On a hot summer’s day in 1990, when I was in my final year of university, I joined the throng of students who went to witness the release of Nelson Mandela. I couldn’t see much from where I was standing, but that didn’t matter. The intensity of the emotion of that day swept through the crowd like a wave, going back and forth and back again. Strangers clung to each other, sobbing – partly from joy, partly from the pent-up sadness and despair that had built up over decades.

To me, the true end of Apartheid happened on April 27, 1994 – the day of South Africa’s first election where people of eligible voting age from all races were allowed to cast a ballot. My parents and I stood in line for eight hours to be part of this momentous occasion.

Those were eight of the best hours of my life. No one minded being in line for so long. Impromptu barbecues sprung up here and there, and everyone was invited. Every now and then, people or groups would break out into song, or start to dance. There were no strangers that day: just millions of people nationwide who were participating in history. For that day, all that mattered was unity and healing.

But the spectre of Apartheid is still very much there. Millions of Black South Africans are still impacted by the damage done by Apartheid rules. The inequities in education will take generations to rectify. Overcrowding from the days of the pass laws persists to this day, along with the associated problems relating to healthcare and access to resources. The poorest 60% of the population, most of whom are Black, own just 7% of the wealth.

My experience growing up as a white kid in Apartheid-era South Africa impacts my life to this day. It is on my mind every time I hear about a Black person in the United States being murdered during a routine traffic stop. It was part of my visceral reaction of grief when George Floyd was murdered. The tears I shed that day were shed for George Floyd, and for the thousands of lives that were taken by Apartheid.

Most of all, it is present in my conversations with my children about race, racism, and white privilege. My husband and I are raising our kids to be agents for change and not bystanders. We encourage our boys to call out racism when they see it, to acknowledge their privilege, and above all, to keep quiet and listen to the voices that really matter – the voices of the people who have been marginalized because of the colour of their skin.

Originally published on June 22,2021 at https://worldmomsnetwork.com/2021/06/22/apartheid-south-africa/.